Why is Frankenstein Still Popular Today?

by Daniel Matthys

An essay written originally for a course at university but never submitted. Obviously it is written for an academic audience but the broad points may be sumerised as such.

1) Frankenstein has enduring popularity from the early 1800s to the present day.

2) This popularity has been explained by Frankenstein’s monster symbolising forces unleashed by humanity that the individual cannot control, war, economic collapse etc.

3) It has alternatively been explained through Frankestein’s monster’s quest to discover who it is and why it was created. In this quest the monster symbolises humanity’s search for these answers.

4) I suggest that both of these explanations in their way are true. The depictions of Frankenstein in film and stage are very different from the book. These depictions seem to endorse the first understanding of the monster above, whilst the book symbolises much more the second explanation.

If you can’t be bothered wading through academic jargon – fear not. I will be using this research for the basis of a post later that will explore some of the implications of this arguement.

The popularity of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein has undeniably persisted into the twenty first century, almost two hundred years after the novel’s first publication. 2014 alone saw the release of the film I, Frankenstein adapted from a graphic novel, a web series Frankenstein MD featuring a female lead, Victoria Frankenstein and in October 2015, 20th Century Fox is set to release another retelling of the classic story entitled Victor Frankenstein. There is little doubt that Frankenstein’s “monster” is one of the most enduring creations of Romanticism, become a staple of 20th and 21st century popular culture. This enduring popularity begs the question of how Mary Shelley’s work still retains vital interest with its audiences. Certainly the novels themes of the responsibilities of scientists, as well of its exploration on what it means to be human, have significant relevance for contemporary audiences in a world of rapid, technological change. Arguably in some ways however, Frankenstein has been overshadowed by the popularity of the iconic character of Frankenstein’s “monster”. Certainly screen and stage adaptions have centred on this character and not always felt obligated to faithfully follow the plot, or the characters, of the novel. Thus any analysis of the novel’s continuing popularity must also centre on the interpretation of Frankenstein’s ‘monster’ in its effort to explain its iconic status both in the novel and its subsequent adaptions.

Lisa Nocks suggests that the “continued popularity of Frankenstein has to do with the parallels between the techno-anxiety of the Industrial Revolution and that on the late twentieth century.”[1] In this analysis Frankenstein reveals the anxieties of humanity left alone in the universe to “grapple with our own inventiveness.”[2] Such anxieties of the dehumanising possibilities of scientific and industrialise man may explain, for example, the success of the depression era screenings, Universal Pictures’ Frankenstein (1931) and The Bride of Frankenstein (1935). The failures of the stock market and the crops, Nocks suggests, may have lead to adaptions of the novel that imply the “human beings might not be doing such a good job at the centre of the universe.”[3] Similarly the novel’s popularity in the present day is a product of the possibility of “realising Frankenstein’s dream”, the realisation that humanity might actually achieve what for Mary Shelley “was just a day dream.”[4] The anxiety such technological prowess invites is that humanity’s abilities may have outstripped its control over its creations so that, like financial markets in the lead up to the Great Depression, humanity might find itself subject to the forces of its making, but beyond its control.

In Nock’s analysis then, at least part of the popularity of Frankenstein in our contemporary society stems from the novel’s role as precursor of the science fiction genre. It allows audiences to explore how technological “developments will (or have) alter(ed) our lives”.[5] Certainly Nocks is not the only one to suggest links between Mary Shelley’s gothic novel and the genre of science fiction. Mark McCutcheon points to similarities in the themes of Frankenstein and science fiction in Canadian cinema, notably the films Videodrome (1983) and Possible Worlds (2000)[6]. As in Nock’s analysis the enduring popularity of Frankenstein stems from the its ability to explore dehumanising elements of contemporary society, but where Nock’s limits her criticism largely to technological developments, McCutcheon extends the theme’s reach to incorporate globalizing trends in worlds of Canadian business and culture. In this understanding the themes of Frankenstein are equally applicable in the world of finance, where McCutcheon notes criticism of the “corporate Frankenstein”[7] from the 1930s, as well as “today’s globalised … ‘war on terror’”[8]. The common ‘threat’ these forces represent in McCutcheon’s analysis is a dehumanisation of people and the impotence of singular identity in a world of vast mechanical forces.

However it is important to note that in Nock’s analysis at least Frankenstein is not adverse to new technologies per se but is rather concerned with the means of obtaining, and the motivations behind pursuing, technological and scientific breakthroughs. In this understanding of the novel it is not technology but “ego which corrupts the best of intentions” leading to “a loss of humanity.”[9] Frankenstein is motivated less by a scientific altruism than the “glory that would attend the discovery” of the “elixir of life”.[10] A parallel might here be drawn with the character of Walton whose pursuit of the North Pole is motivated by the same “madness” and desire for “glory” that pushed Frankenstein to create his ‘monster’.[11] It the motivations and the flaws of Frankenstein’s character according to Nock that leads to the tragedy of the story. Notably the creature is not portrayed as intrinsically evil or brutish but rather it is the creature’s abandonment by his father that leads him to “adopt the ‘fallen son’ character of Satan in Milton’s Paradise Lost and … seek revenge.”[12] It is the failure of Victor Frankenstein to provide for his creation, a failure that stems from the selfish motivations of his experiment, which for Nock represent the enduring message of the novel. The “subtle lesson … that there must be some limit, not in how far we go, but in how we go.”[13]

The exploration of human identify present in Frankenstein might then offer another take on the continuing popularity of the novel. Certainly the ‘monster’s’ characterisation in the novel is better placed to explore these ideas than some of the cruder adaptions of its character particularly those seen in Universal Picture’s Frankenstein and The Bride of Frankenstein. In fact the ‘monster’ of Shelley’s novel becomes almost a stand in for humanity in general. The creature, abandoned by his creator asks, “‘Who was I? What was I? Whence did I come? What was my destination?’ as if to echo Frankenstein’s [own] search for the origins of life.”[14] In a similar way the novel’s subtitle, the modern Prometheus, and its allusions to Milton’s Paradise Lost, suggest a vision of humanity created “wantonly,”[15] without consent, and abandoned in an alienating universe to grope for answers. Like his own creation, Prometheus, or Satan, Frankenstein himself, in his quest for the elixir of life, may be seen as warring with the “omnipotent God” who created him.

Outside of the broad questioning of the purpose of creation Frankenstein also incorporates Enlightenment ideas of the identity of the human person. Most notably the creature is portrayed as ‘naturally virtuous,’ he becomes violent “only after he is repeatedly rejected by society, and after Victor refused his request for a companion.”[16] The exploration dehumanisation in the novel thus centres on the role of community and friendship in creating an environment where natural virtue might flourish. Similar ideas lie at the roots of the flaws of the character of Victor Frankenstein and Walton. Both men are introspective, isolating themselves from society and friends, creating a “paradoxical situation” where their isolation gives them the “self absorption and concentration necessary to reach [their] goals”[17], but also creating the circumstances that allows them to deny any responsibility to a broader community. This notion of human identity becomes relevant to the popularity of the novel in contemporary society particularly when the isolating tendencies of new technologies, like the Internet are considered. Shelley’s Frankenstein then retains its relevance as it explores the divisions and dehumanising elements of modern technology.

We might accept with Nock that the message of the novel is, not so much a warning tale of the excesses of science, but rather a tale of the personal flaws of a single scientist. However this interpretation of Frankenstein does not necessarily account for the continued popularity of the novel. Frankenstein occupies an unusual position in the literary canon in that its popular conception has been considerably shaped by adaptions of the work. The first stage adaption of the novel, Richard Peake’s Presumption; or the Fate of Frankenstein, appeared just five years after the novel’s début and by 1985 the dramatic adaptions numbered at least fifty-eight.[18] To ignore these adaptions would in accounting for the novel’s continued popularity would be mistaken as provide many with their first, sometimes their only, encounter with Shelley’s creation. Steven Forry, in his examination of the early adaptions, suggests that they “share the responsibility for shaping … popular conceptions of the novel.”[19] In particular Forry notes the early adaptions “reintroduced the supernatural” into Shelley’s story, reorienting the messages of the novel towards the more religious ‘morality tale’ of the type of Dr Faustus.[20] In such a reinterpretation it is difficult to see how the more nuanced message of the failure of the individual scientist might survive. In these interpretations it might be argued characters are reimagined as popular archetypes, the reckless scientist/magician, the brutish creature and the creature’s tragic victim.

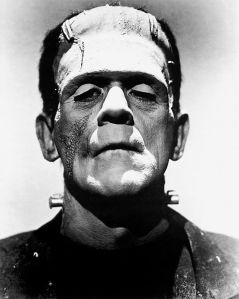

It might be argued in fact, that the popularity of Frankenstein owes less to its exploration of the subtle nuances of character and more to the broad themes of forbidden knowledge and the perils of science and technology. Though we might agree with Nock that the novel does not place any reins in how far human thought may go, it is difficult to see how this idea survives popular conceptions of the ‘monster’. The unwieldy, bolted flesh and the brutish nature of the iconic depiction of the ‘monster’ bears little resemblance to the talking, reasoning creature who delights in hearing stories of man, at once “virtuous and magnificent” and “vicious and base”.[21] This iconic figure is not the tragic character of the novel but simply the unfortunate, and inevitable, result of forbidden science. Such techno-anxiety about new science, as we have already seen, might play a significant role in the popularity of the character, but in these adaptions the exploration of human identity and the flaws of characters definitely take a back seat. By looking at the popularity of Frankenstein through its adaptions then, the work’s popularity can be, at least partly, attributed to a conservative validation of caution and limits to technological progress.

The popularity of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein then is a multifaceted phenomenon. Certainly the themes of the novel explored by Nock and McCutcheon retain their relevance in contemporary society, as they must have done both in Shelley’s industrialist age and amongst later audiences experiencing social breakdown in the Great Depression. The nuances in the novel’s exploration of the human person and his/her quest to explore the universe identified by Nock obviously resonate as much today as they have in the past. However, to ignore the adaptions of Frankenstein and in particular their characterisation of the ‘monster’ would be mistaken. In these adaptions in particular the techno-anxiety occasioned by technological breakthrough leads to an exploration of the perils of ‘forbidden knowledge’ and a discussion of the negative aspects of scientific thought. This theme with retains also retains its relevance in contemporary society must be properly accounted for if the novel’s popularity is to be justly assessed.

[1] Lisa Nock, “Frankenstein in a Better Light” in Journal of Social and Evolutionary Systems, 1997, Vol.20(2), page 138

[2] Lisa Nock, “The Golem: Between the Technological and the Divine” in Journal of Social and Evolutionary Systems, 1998, Vol.21(3), page 297

[3] Nocks, “Frankenstein in a Better Light”, page 149

[4] Nock, “Frankenstein in a Better Light”, page 151

[5] Nock, “Frankenstein in a Better Light”, page 151

[6] Mark McCutcheon, “Frankenstein as a figure of globalization in Canada’s postcolonial popular culture,” in Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, October 2011, Vol.25, No.5, pp. 731-742

[7]McCutcheon, “Frankenstein as a figure of globalization”, page 733

[8]McCutcheon, “Frankenstein as a figure of globalization”, page 734

[9] Nock, “Frankenstein in a Better Light”, page 150

[10] Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, Penguin Books, Melbourne, 2009, page 37

[11] Shelly, Frankenstein, page 21

[12] Nock, “Frankenstein in a Better Light”, page 153

[13] Nock, “Frankenstein in a Better Light”, page 154

[14] Eleanor Salotto, “’Frankenstein’ and Dis(re)membered Identity” in The Journal of Narrative Technique, Vol. 24, No. 3, 1994, page 192

[15] Shelly, Frankenstein, page 165

[16] Nock, “Frankenstein in a Better Light”, page 150

[17] Nock, “Frankenstein in a Better Light”, page 150

[18] Steven Earl Forry, “The Hideous Progenies of Richard Brinsley Peake: Frankenstein on the Stage, 1823 to 1826” in Theatre Research International, Vol.11, Issue 01, 1986, page 13

[19] Forry, “The Hideous Progenies,” page 14

[20] Forry, “The Hideous Progenies,” page 21

[21] Shelly, Frankenstein, page 143